Parts of a Whole - Parasha Tetzaveh

In this excellent podcast episode, Abigail True explains the juxtaposition of the holidays on the Jewish calendar, and how each one corresponds to the one across the calendar from it.

Repost: The Jewish Theological Seminary, "Parts of a Whole", Abigail Treu. 2013

In this excellent podcast episode, Abigail True explains the juxtaposition of the holidays on the Jewish calendar, and how each one corresponds to the one across the calendar from it.

In this, she draws amazing insights for the holidays of Purim and Yom Kippur, and how both are necessary for the full expression of the human experience.

Excerpts:

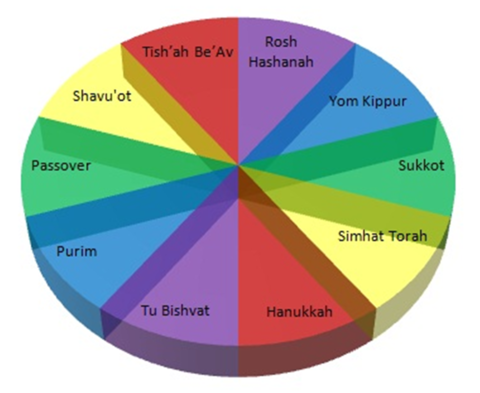

Seen as a two-dimensional whole, we understand that certain themes experienced from a particular angle on one holiday are revisited from another angle on another holiday; and, in fact, that those themes and holidays lie directly opposite from one another in the calendar cycle.

So, for example, Passover and Sukkot, both in green above, our two weeklong holidays celebrate (a) the beginning of the harvest and its culmination and (b) the Exodus from Egypt and God’s protection during the ensuing years of wandering. One occurs in the spring; the other, directly opposite, in the fall. Or Hanukkah and Tish’ah Be’Av, in red on the chart above: one is a celebration of light during the shortest, darkest days of the year, and the other is a day of darkness during our brightest season. One celebrates miracles and military victory, and the other marks tragedies and political defeat; one, the rededication of the Temple, and the other its destruction. If we celebrate only Passover, but not Sukkot; only Hanukkah, but not Tish’ah Be’Av, then we experience only a small portion of the reality and the wholeness that the totality of the holiday cycle enables us to live out.

This brings us to the holiday so soon upon us, Purim. Since Purim sits directly across from Yom Kippur on our chart above, we wonder: what connects these two most disparate of holidays? Yom HaKippurim k’purim puns the Zohar (“Yom Kippur is like Purim,” a pun on the close sound of the Hebrew), and, ever since this was written in the 13th century, rabbis have wondered just how the two might be alike—what the Zohar could have meant.

At its most superficial, we understand the two to be diametric opposites. Yom Kippur is solemnity; Purim is lightheartedness. On Yom Kippur, we fast and afflict our souls; on Purim, we feast, drink, and tell jokes. If on Yom Kippur we take ourselves seriously, on Purim we mock ourselves and make light of life.

More deeply than this, Yom Kippur is a day in which we insist that there is a God who sits in judgment of us. It is the day on which we comfort ourselves with the awesome yet soothing consolation that there is a God watching over us, a God who cares about what all of us do as individuals and, not unlike Santa Claus, a God that keeps track of who is naughty and who is nice—and also that this God has the power to grant us life. So if we give full expression to our consciences, then we will be granted teshuvah, the chance for more time to do things better.

On Purim, we insist just the opposite. We read the Megillah, which does not mention God even once. We sense that the miracles of the story come about by nature or coincidence; that we have only ourselves to rely on because life is a game of lots (purim), and our fate has only to do with the luck of the draw. Purim is the holiday in which we declare that life is chaos, God seems absent from our lives, none of us knows what is right or wrong (the Talmud suggests we drink until we cannot distinguish between Haman and Mordecai [BT Megillah 7b]), and we celebrate because we are alive and must adopt an attitude of making the best of it.