Render Unto Caesar: The Rabbinic Discourse on Idolatrous Coins

When Jesus said, “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s,” he wasn’t only sidestepping a political trap, he tapped into a rabbinic debate on coins bearing idolatrous images. But beneath the surface lies a deeper theme: coins as symbols of the soul, each human being stamped with the divine image.

In Matthew 22:21, Jesus was famously asked about paying taxes to Caesar.

Jesus's answer is often viewed as a clever response to a political trap, emphasizing the separation of civic and religious responsibilities. In this view, the focus anchors on the tension between Jesus and certain Pharisees and Herodians of his day.

It's true, taxes had long been a difficult part of daily life in the Roman Empire, but there is more to this encounter, and perhaps a deeper meaning, too. One that brings us back to the earliest ideas in the creation narrative.

The Context of Coins

Aside from the trap of the discussion, there are underlying dimensions at play. One aspect of the question is on the permissibility of using coins bearing idolatrous images. This was an intra-Rabbinic discussion in Jesus's time and would likely have been an everyday question for religious people.

The reason: the Torah explicitly forbids the creation or worship of images, as these are most often associated with other idolatrous practices. In Exodus 20:4, we read:

You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them.

Roman coins, like the denarius mentioned in the Gospels, often featured the image of Caesar.

In this particular time, the Emperor was Tiberius¹. Though Tiberius did not accept the excessive adornment of divinity, as other Emperors had, many Romans saw him as a continuation of the divine position of Emperor. As a result, this was within the realm of idolatry.

To add to the complexity, the Torah also prohibits bringing impure or "dirty" money into the Temple², precluding money earned through immoral means.

It was well known that the Romans used their money for a wide range of impure and idolatrous activities. In addition, many of their coins bore the image of idols and even nudity. Thus, Roman coins posed a multi-layered problem for Torah-observant Jews.

To this day, Israeli coins do not feature images of people.

The Tyrian Coin

On the other hand, Exodus 30:13 required a half-shekel offering in the Temple, but does not explicitly say which type of shekel to use.

After discussion, the Sages chose the Tyrian coin as acceptable for Temple use, in part, because it was made of pure silver. But this decision was not without controversy.

The Tyrian coin also had the image of an Eagle on them. After some discussion, the Sages distinguished between images (statues, coins, etc) intended for decoration and those for worship. The Tyrian Eagle was deemed to be merely decorative.

The Moneychangers

To protect the purity of the Temple, the Sages instituted the money changers, Shulchanim (שלחנים). Their job was to post around the Temple courts to exchange various currencies for the Tyrian shekel.

This would have been helpful for diasporic Jews and visitors from various regions outside of Israel to exchange money for use in worship.

Most are familiar with the story of Jesus overturning their tables. Some degree of the moneychangers appear to have been corrupted by Caiaphas's leadership in the first century, implementing high exchange fees, and letting improper coins in the Temple treasury at times.

Despite having a bad reputation in the New Testament, the institution itself was important.

Everyday Currency

Nevertheless, a solution existed for the Temple, but the problem was not totally resolved for everyone else. Would using idolatrous coins make one impure or block holiness? It is a logical question.

Total avoidance would be too burdensome for the common people, plus the Romans would not be fond of a competing financial system within their boundaries. There needed to be some middle ground.

Later writings would help solve problems for future generations; however, these discussions were still relatively fluid in the first century.

The Talmud shares a related story from the 3rd century:

There was an incident involving a certain heretic who sent a Caesarean dinar to Rabbi Yehuda Nasi on the day of the heretic’s festival. Rabbi Yehuda said to Reish Lakish, who was sitting before him: What shall I do? If I take the dinar, he will go and thank his idol for the success of his endeavor, but if I do not take the dinar, he will harbor enmity toward me.

Reish Lakish said to him: Take it and throw it into a pit in the presence of the heretic. Rabbi Yehuda said: All the more so, this will cause him to harbor enmity toward me. Reish Lakish explained: I said, you should throw it in an unusual manner (drop it), so that it looks as though the dinar inadvertently fell from your hand into the pit. - Avodah Zara 6

Rabbinic Resolutions

To avoid the economic hardship on the Jewish people, and promote peace among the Romans, the Sages allowed the use of coins for everyday taxes and purchases with a few stipulations.

For example, people should not gaze at or admire the images. In more strict observance, some should think about how we interact with the money, as in the story above, lest we give the impression we are partaking in unholy activities.

An even more strict example is that of Rabbi Menachem bar Simai who was praised for his practice of avoiding looking at the coins altogether.³

Other questions likely included in this discussion, might have been:

- Could these coins be swapped on Shabbat?

- If Roman coins are associated with idolatry or immorality, do Jews share guilt and spiritual punishment for using them?

- Though Jewish law encourages Jews to be law-abiding citizens, is there a time to disobey rulers when secular laws violate Torah law?

A Deeper Understanding

By highlighting Caesar's image, Jesus evoked the Torah prohibitions, provides practical advice, and avoids getting into conflict with the Romans. In the final analysis, the Sages and Jesus largely agreed on the economic aspect, but there is a deeper lesson between the lines.

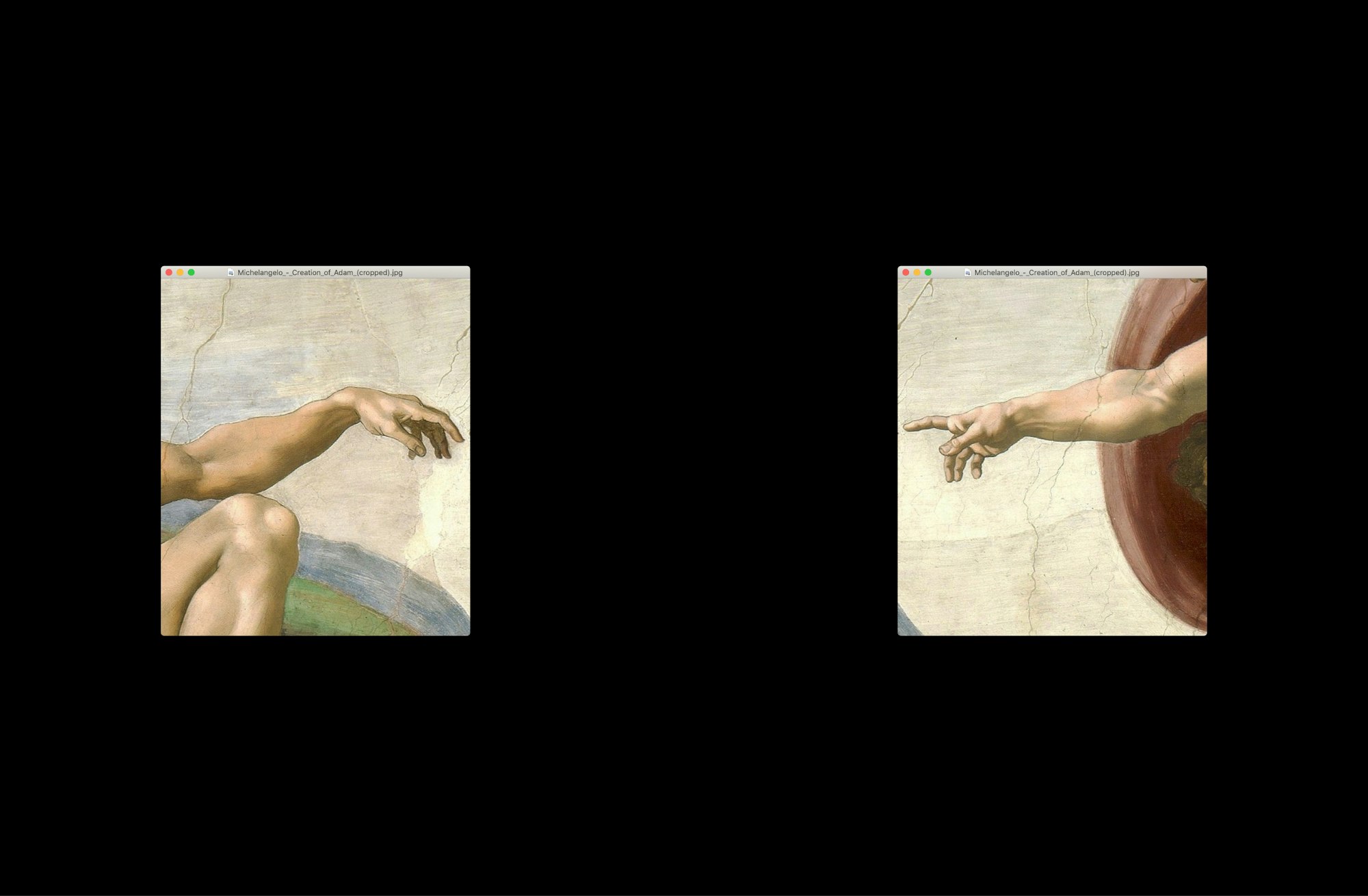

This discussion taps into a common trope in the Rabbinic literature regarding the image on coins and the creation of humankind⁵.

In other places, the Creator is described as a Lender, a banker, who mints coins and lends them out.⁶ Thus, people are likened to coins, minted from with the Image of the Creator (Tzelem Elokim). This idea ties back to Genesis and the creation of Adam.

In the Talmud, Sanhedrin 37 (Mishnah 4) we read;

... the Holy One, Blessed be He, as when a person stamps several coins with one seal, they are all similar to each other... He stamped all people with the seal of Adam the first man...

Jesus's teaching seems to draw from these same idea. His teaching was more than clever advice; his call was to remind his listeners of their creation and purpose, those made in the image of G_D.

The coin motif is also applied to the mystical level, representing our Soul⁷ given to use at the beginning of life. Like borrowers, we will deposit our soul back with the Creator at the end of life. Jesus references this in his last words⁸.

"Father, into your hands I commit my soul"

So we learn, even these simple exchanges in the Gospels can serve as a portal to a universe of spiritual themes and lessons.

To me, this exchange is less about taxes and more about reconnecting with our created purpose, to live into the likeness of our Creator.

Doing the work of He, Whose image we bear. As Jesus states in another place:

“Do not work for the food that perishes, but for the food that endures to eternal life, which the Son of man will give to you. For on him G_D the Father has set his seal.”” - John 6:27

This lesson is a familiar one quoted elsewhere:

You should love the Lord your G_D with all of your heart, all of your soul, and all of might.

Want to Learn More

Notes:

¹ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tiberius

² "You shall not bring the fee of a prostitute or the pay of a dog into the house of your G_D in fulfillment of any vow, for both are abhorrent to your G_D." - Deuteronomy 23:19.

³ Pesachim 104a

⁵ See: Sanhedrin 38a; Rashi on Genesis 1:27

⁶ Pirke Avot 3:16

⁸ Luke 23:46

🌱 Enjoying what you’re discovering? 🌱

Support The Hidden Orchard and help us grow and share with others.