The Death of the Firstborn

The Death of the Firstborn is one plague that some struggle to come to terms with. Many have asked, "For what purpose did G_D kill so many innocent people?" While this might be rationalized as payback for the death of the Hebrew infants in Exodus 1, closer inspection indicates a deeper message.

Years ago, while studying, I came across numerous insights into the Exodus story that are captured in the Torah - insights I imagine to be obvious to students of Egyptology.

Interwoven into the narrative, there seem to be nuanced references to Egyptian views of death, the afterlife, the funerary heart-weighing customs, and - as we will explore in this work - particular deities targeted by the plagues.

On a simple level, the plagues and afflictions dealt to Egypt seem to be straightforward punishments or hardships intent on swaying Pharoah's mind.

From start to finish, Jewish tradition tells us that the afflictions spanned 12 months¹, bringing us back to the month of Nisan for the final act, the Death of the Firstborn.

Most of these plagues might be considered reasonable consequences of Pharoah's stubbornness. This final plague, however, the Death of the Firstborn - is one that some struggle to come to terms with. Many have asked, "For what purpose did G_D kill so many innocent people?"

While this might be rationalized as payback for the death of the Hebrew infants in Exodus 1, closer inspection indicates a deeper message.

Early Signs of Trouble

As hinted above, Jewish tradition teaches that each of the (10) plagues inflicted upon Egypt was an assault on a particular deity. Strangely, despite the vast destruction of the previous afflictions, the slaughtering of a lamb seems to be treading on new ground.

There are early warning signs of this in Moses's discussions with Pharoah. We get the sense that the specifics of G_D's commandments for the lamb may be triggering to the Egyptians:

Then Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron and said, “Go and sacrifice to your G_D within the land.” But Moses replied, “It would not be right to do this, for what we sacrifice to our G_D is an abomination to the Egyptians. If we sacrifice that which is abominable to the Egyptians before their very eyes, will they not stone us! - Exodus 8:21-22

Moses, raised amid Egyptian culture, understood that offering a lamb (or a ram) would be extremely troublesome if the Egyptians were to witness this.

With this knowledge, Moses suggested no less than a three-day journey to prevent the Egyptians from seeing what they were about to do².

Why so far away? What was it that the Egyptians could not see?

In the Rabbinic literature, we learn that the animal to be slaughtered, a lamb, represented a particular Egyptian deity.

This begins to help us understand Moses's hesitation. But it gets deeper. We may uncover a new dimension of how the lamb is intricately connected to the Death of the Firstborn.

The Month of Nisan

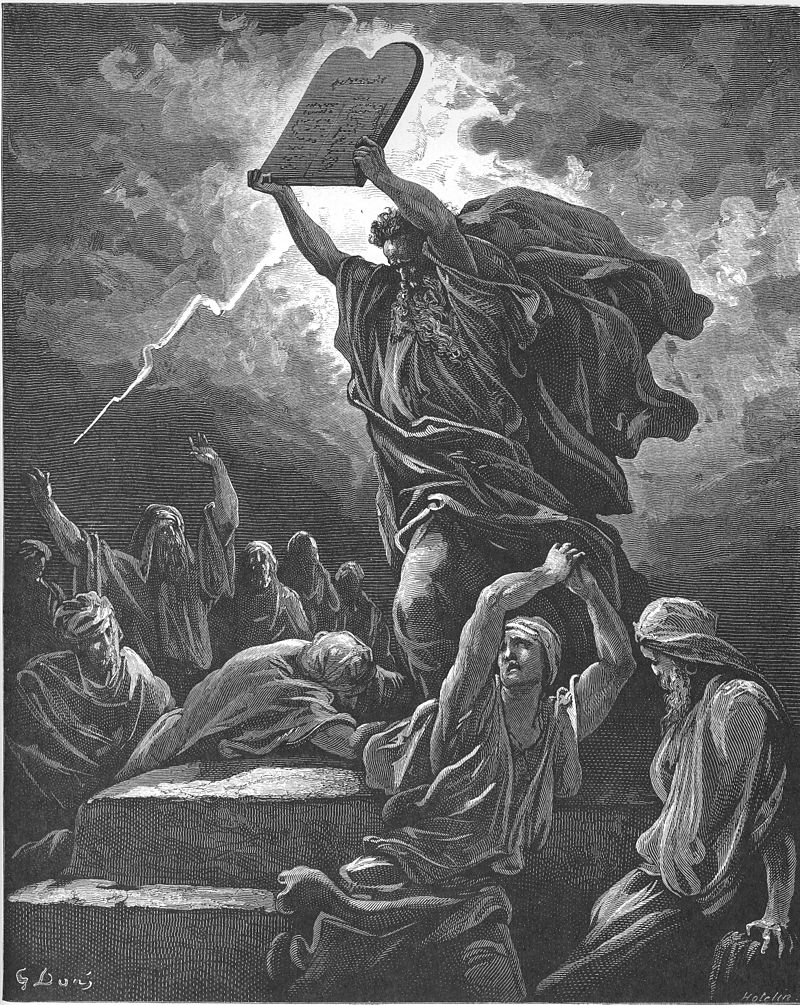

Think back to the story in Exodus; the Death of the Firstborn was the catalyst that ultimately broke the back of the nation of Egypt. Through this event, an opening was created for the Israelites to flee. It also seemed to sever the Egyptian bloodlines in a significant way.

This particular affliction happened in the month of Nisan, according to the Jewish calendar.

The word for miracle (נס) shares the same root as Nisan (נִיסָן), hinting that Nisan is associated with miracles. The Ancient work, Sefer Yetzirah, explains that this is because Nisan is the month most aligned with the Name Y-K-V-K, creating a powerful flow of Divine energy at this time.

In short, the Mazal of Nisan is favorable for great miracles and occurrences that can bend the laws of nature as we think we know them.

Commentator, Nachmanides³, tells us that the Nisan coincided with the Egyptian astrological sign of Aries. Aries, depicted as a ram, was Egypt's primary astrological sign⁴. In addition, Aries was at peak strength in the middle of the month when the Passover occurred.

More than a random affliction, this event seemed to denote a timely cosmological showdown! And, it gets better, as we will see shortly.

Nachmanides continues⁵:

The astrological sign of Aries, the ram, is of course, at its greatest strength during Nisan, when it is a rising sign. Slaughtering a lamb demonstrated that we did not leave Egypt by force but by Divine decree.

Adding to this drama, commentator Rabbeinu Bachya tells us⁶:

... G_D ordered the lamb to be slaughtered during this month to demonstrate that this animal that they considered their symbol of success could not even protect itself, much less those who worshipped it.

The Pesach offering was not a sin offering, as many might think. On one level, this offering represents an active demonstration of faith in G_D, and a flagrant rejection of the Egyptian religious system.

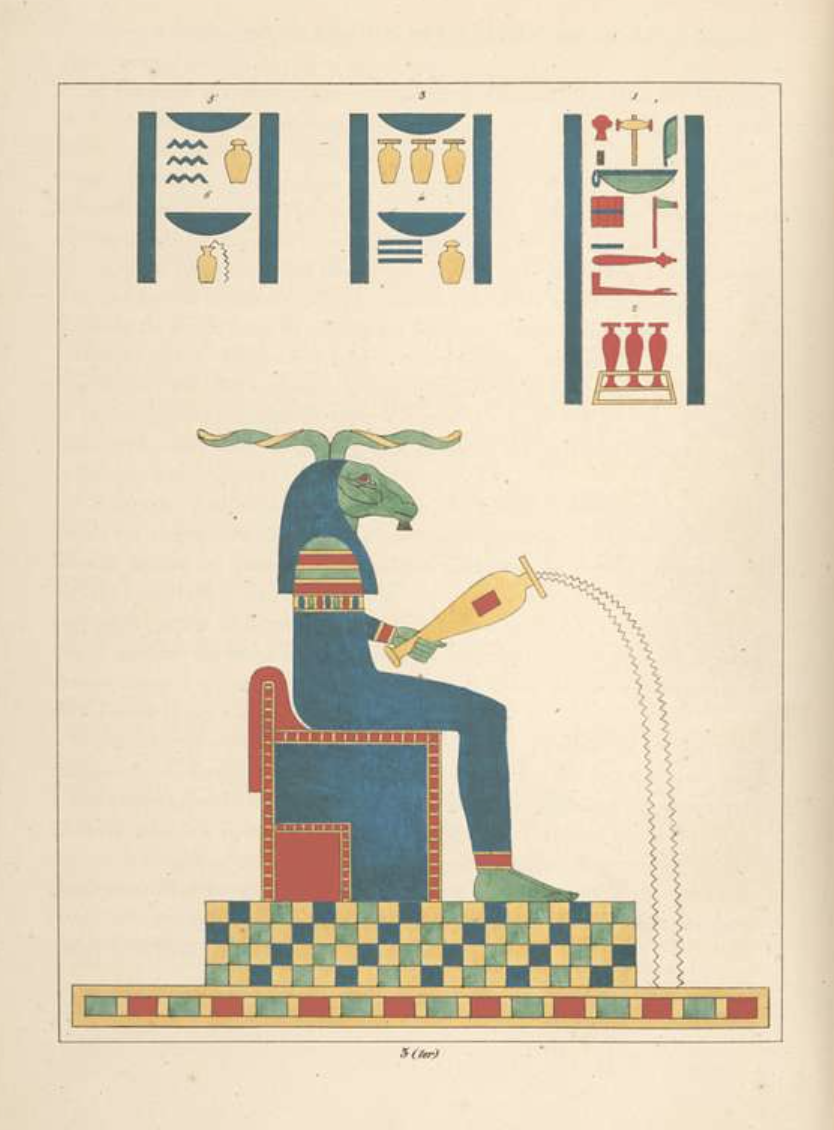

Khnum - the Ram god

Indeed, looking through ancient Egyptian records, the deity associated with the ram, is known as Khnum.

Khnum, like a few others, represented an aspect of fertility and life. What is most striking to me is that Khnum was believed to have been the creator of humankind according to Egyptian mythology.

Known as the "Divine Potter," Egyptian tradition recounted how he fashioned humans from the mud of the Nile. Another name he was known by translates as "the lord of created things from himself." As one source shares:

He [Khnum] was responsible for the creation of humans from the clay of the Nile River, then, he held the clay statues towards them to Ra "The Sun god", to give them life then the souls of humans were placed in the womb to then breathe and exist on earth.⁷

Assuming Khnum was indeed the deity in focus, it seems G_D wanted to make it clear Who created the world, had the power to give and take life, and by Whose hand the Israelites were freed.

This show of force was for a specific purpose. G_D indicated this idea, more than rescuing the Israelites, that He wanted to prove that He was G_D for all.

And the Egyptians shall know that I am י-ה-ו-ה, when I stretch out My hand over Egypt and bring out the Israelites from their midst.” - Exodus 7:5

I wonder how much depth is hidden in these writings that we lack the context to grasp. How many more allusions are captured in the Torah that an original audience might have inherently understood?

Nevertheless, the dichotomy resonates through our modern times; where seeking the Creator might be counter-cultural, and acts of faith might be perceived as defiance.

You might also like these articles...

Notes:

¹ Rabbeinu Bahya, Genesis 8:14

² Exodus 8:23

³ Nachmanides https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/moshe-ben-nachman-nachmanides-ramban

⁴ Nachmanides on Ex. 8:22

⁵ Nachmanides on Exodus 12:2-3

⁶ Rabbeinu Bachya on Exodus 12:7